Whenever we buy something from Amazon, Etsy, or some other online shop, we always want to check the reviews to find out if we’re getting a good deal. Typically, such websites may have a system where each user can write one review for a product, and award it some numerical score, such as a 1-to-5-star rating. The site will then tally up all reviews for a product, find a mean average, and report this as the overall rating for the product.

However, we must contest with the fact that while all reviews contribute equally to the average score, not all reviewers are equally trustworthy.

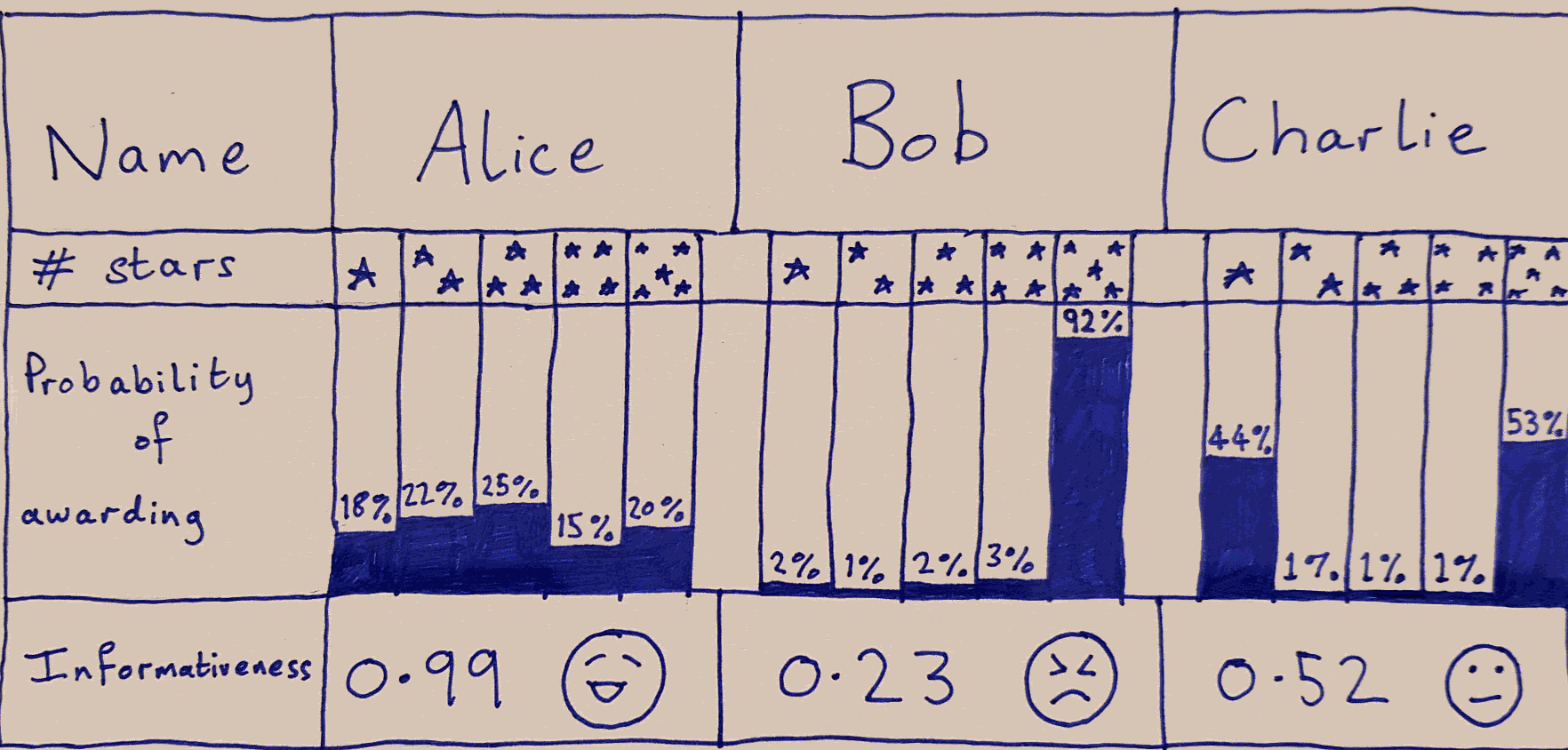

For example, suppose Alice and Bob are looking at reviews for a new blender. Alice might deeply consider every aspect of each product, testing it in a variety of different situations, with fruit, veg, and ice, and give very careful thought as to what might constitute the boundary between a 3-star and a 4-star rating.

Bob, on the other hand, might just be rabidly excited about everything he gets his hands on, and award 5-stars to everything he buys.

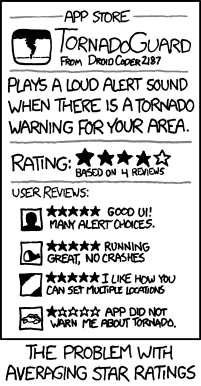

The problem with valuing all reviews the same is highlighted in this xkcd comic:

Ideally, we would probably want to assign a weight to each reviewer that quantifies how informative their reviews typically are. Fortunately, the mathematical notion of information (also known as entropy) perfectly fits this requirement.

Information

The intuition behind information is pretty simple:

The less likely a given score is, the more information it conveys.

So if Alice only awards a 5-star review to one product per year, then any product that gets it must be really good. A 5-star review from Alice therefore tells us a lot about the quality of a product.

However, a 5-star review from Bob tells us nothing. It could be great or it could be terrible, no-one knows.

For technical reasons (explained here) the information content of a particular rating is proportional to the negative logarithm of its probability. So if a Alice gives a 5-star review with probability $p(5)$, then we can say that the information content of such a review is

$I(5\star \text{review}) = -\text{log}\left[p(5)\right]$

Suppose we want to know the average informativeness of a reviewer. If we could assign a number to this, then we could consider more informative reviewers to have more “votes” towards the total score. To find this, we average over the probabilities of them awarding each number of stars:

$I(\text{Reviewer}) = -\sum_{i=1}^5 p(i) \text{log}_5\left[p(i)\right]$

According to this equation, a reviewer that awards each rating 20% of the time is the most informative on average (with $I(R)=1$), and someone who gives a single rating 100% of the time is the least informative (with $I(R)=0$). Someone who gives 1-star and 5-star reviews 50% of the time each is partially informative (with $I(R)=0.43$).

Entropy

This formula might look familiar to those who have studied thermodynamics. It is the notion of entropy that describes how disordered a system is. We can think of this as the unpredictability of the reviewer. It is hard to predict Alice’s score before she makes it, but very easy to predict Bob’s score. We can therefore think of Alice as being chaotic, and Bob of being very ordered.

It might seem almost paradoxical, but this means that chaotic systems contain a lot of information, and ordered ones have no information!

Bayesian Statistics

So we might think that we just need to identify a reviewer R, calculate $I(R)$, then weight all of their reviews by this value. However, if we do this, people who have not made many reviews may appear to have a lower information than usual!

Suppose that Doug is a clued-up reviewer, and that, given the chance, would rate 20% of products as 1-star, 20% as 2-star, and so on. But if he has only written one review, then his spread of reviews will be fully concentrated in one column!

This will mean that his informativeness will be evaluated as zero! We need a way to evaluate Doug’s informativeness, while simultaneously taking into account that he will probably be better informed than he initially seems.

Simplifying the problem

Before we go any further, we will simplify the problem to make the calculations easier. Suppose that instead of rating on a 5-star system, we have a 2-star system. Any product may be either awarded 1-star or 2-stars.

For a given reviewer, R, let $Q_R$ be the probability that he awards 1-star to any given product. Note that this is not the same as the number of products to which he has awarded 1-star divided by the number of products he has reviewed (which would be equal to either 0 or 1 after 1 review). Instead we can think of it as the ratio of 1-star reviews that he would award after making an infinite number of reviews.

Of course, from this we can determine that the probability of awarding 2-stars is $1- Q_R$, so each reviewer is described by only one free parameter.

So we want to predict $Q_R$ for a reviewer. In a situation where we have not seen any of his reviews, the sensible thing would be to assume that he behaves pretty similar to everyone else.

Let’s assume that on average $Q_R$ = 0.5. Moreover, we shall assume that the distribution of $Q_R$ over different reviewers is approximately normal, with $\sigma^2 \ll 1$ , so that we can safely ignore the effects of $Q_R$ existing on a bounded domain. That is to say:

$p\left(x<Q_R<x+\text{d}x\right) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma}e^{-\frac{(x-0.5)^2}{2\sigma^2}} \text{d}x$

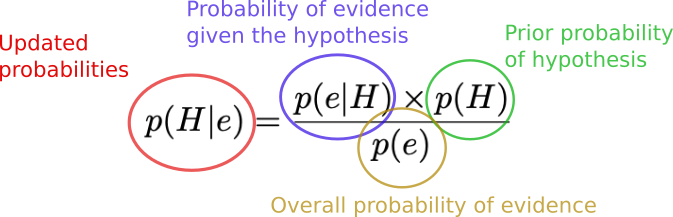

Bayes’ Theorem

So our initial assumption, given no reviews, should be that $Q_R$ = 0.5 . Once our reviewer starts awarding more 1-star or 2-star reviews, then we can change our estimation accordingly. So we have a prior probability, some evidence, and a resulting posterior probability.

This kind of situation is the perfect setting to apply Bayes’ theorem:

Our hypothesis will be something of the form “$Q_R = x$”. Also, since we know that all independent probabilities should add up to 1, we can rewrite the denominator as:

$p(e) = \int_0^1 p(e|Q_R=x) p(Q_R=x) \text{d}x$,

where, when $\sigma \ll 1$, we can write $\int_0^1 \approx \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}$ to make it analytically solvable. However, in practice, we will often perform this integration numerically.

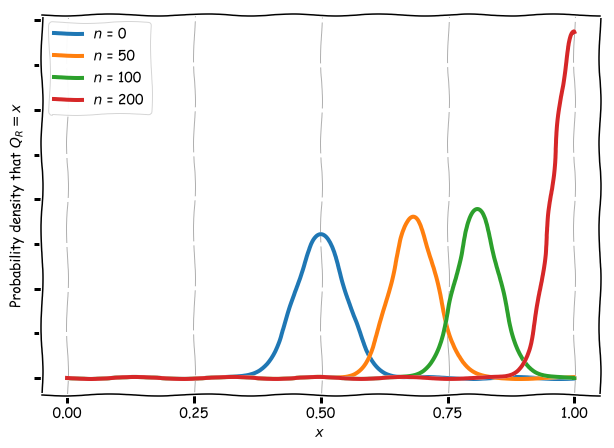

Suppose that our reviewer makes 10 1-star reviews. Is it likely that he is a one-track-minded reviewer, but not definite. If he makes 200 such reviews, then it is practically certain. In the below graph we can see this quantified. We consider different reviewers, where each one has awarded n 1-star reviews and zero 2-star reviews. The height of the graph is the probability density that our reviewer has $Q_R = x$ for different values of x on the horizontal axis. We take the peak of each graph as our Bayesian estimate for $Q_R$ (the maximum likelihood estimator).

In contrast, the frequentist estimate for $Q_R$ is just $n_1/(n_1+n_2)$, where $n_i$ is the number of i-star reviews.

Application to some simulated data

Suppose we have a situation where people who only give a few reviews are, in reality, more discerning that those who give a great many. This is certainly a believable situation – unless someone is a professional critic, it is likely that the more reviews they write, the less time and care will be taken on each review.

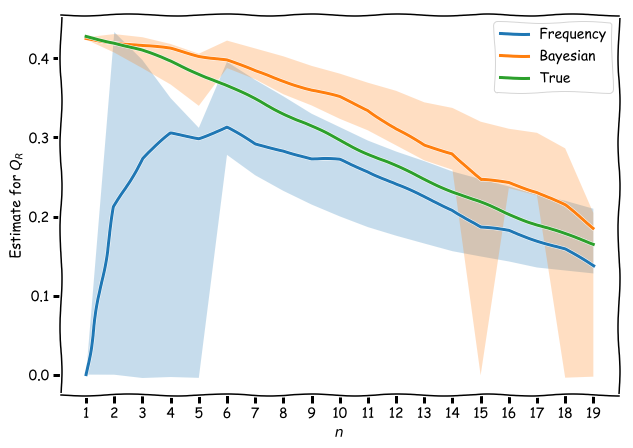

I created a simulated dataset of reviewers that followed this behaviour, where $Q_R$ started at 0.5 for reviewers with a small number of reviews, n, and decreased as n increased. I plotted the average estimation of the informativeness of these reviewers, judged by both the frequentist and Bayesian interpretations. As we can see, the Bayesian estimate tracks the true values much more closely. Additionally, we get a much wider confidence interval at low $n$ in the frequentist approach, since a lot of the time, we will estimate a reviewer as having zero informativeness.

Of course, one might argue that the Bayesian approach depends on a good initial guess as to the probability distribution (which here we set to a narrow Gaussian). Of course, in any real-life scenario, we will usually have some hypothesis as to how the data might be distributed, and a reasonable guess is better than no guess. Besides this, there are various methods for choosing a good prior that make the most minimal set of assumptions of the data.

So we can see that it may very well be important to value the informativeness of our reviewers. But don’t forget to think like a Bayesian when you do!