I recently spotted a new competition on the fantastic website drivendata.org, which is sort of like kaggle for humanitarian causes. The competition provided the results of a questionnaire given to about 26,000+ people at around the time of the bird-flu epidemic, with the aim of trying predict whether or not someone will get a vaccine for the H1N1 bird-flu, and whether they will get a vaccine for the seasonal flu.

The questionnaire asks yes/no questions such as “Have you avoided touching your eyes, nose, or mouth?” and “Have you frequently washed your hands or used hand sanitiser?”, as well as opinion questions such as “What is your level of worry of getting sick from taking H1N1 vaccine?” and “What is your opinion about seasonal flu vaccine effectiveness?”, which are rated from 1 to 5.

As is the usual procedure for a data science competition of this form, I started off by doing a bit of exploratory analysis, before loading up a bunch of different models from sklearn and keras, fitting them to the data, doing a bit of optimisation, and choosing the one with the best value for the metric (which in this case was the AUC, or the area under the ROC curve). I found that a gradient-boosted tree was best (as often turns out to be the case in competitions, which have medium-sized data sets and demand very high accuracy).

But does this mean that we should go to the doctors, nurses, and public health officials with this model to help them decide where to target public health announcements? Probably not.

Often in healthcare, as in science more generally, getting the highest possible accuracy on a problem is not the most important factor. We don’t just want to get results, we want to understand them. A neural network may be extremely accurate, but it cannot be reverse engineered. You have to simply input the data and trust the output. In healthcare, where lives are on the line, handing off accountability to an algorithm in this way is often not acceptable.

In fact, standard linear or logistic regressions are widely used in healthcare for exactly this reason. They are very easy to understand. One can easily take the model and understand the importance of the different features at a glance. A doctor might easily see: “Ok, this person is likely to get a vaccine because they have a child under six months old, whereas this person is very likely to get it because they are a healthcare worker with a chronic medical condition.” They can then use this information along with more individualised information that they know about a patient to make a decision on whether to push them to get a vaccine. This highlights an important fact:

A simple algorithm allows doctors and nurses to use the model to inform their own decision-making. A complex algorithm must do the decision-making by itself.

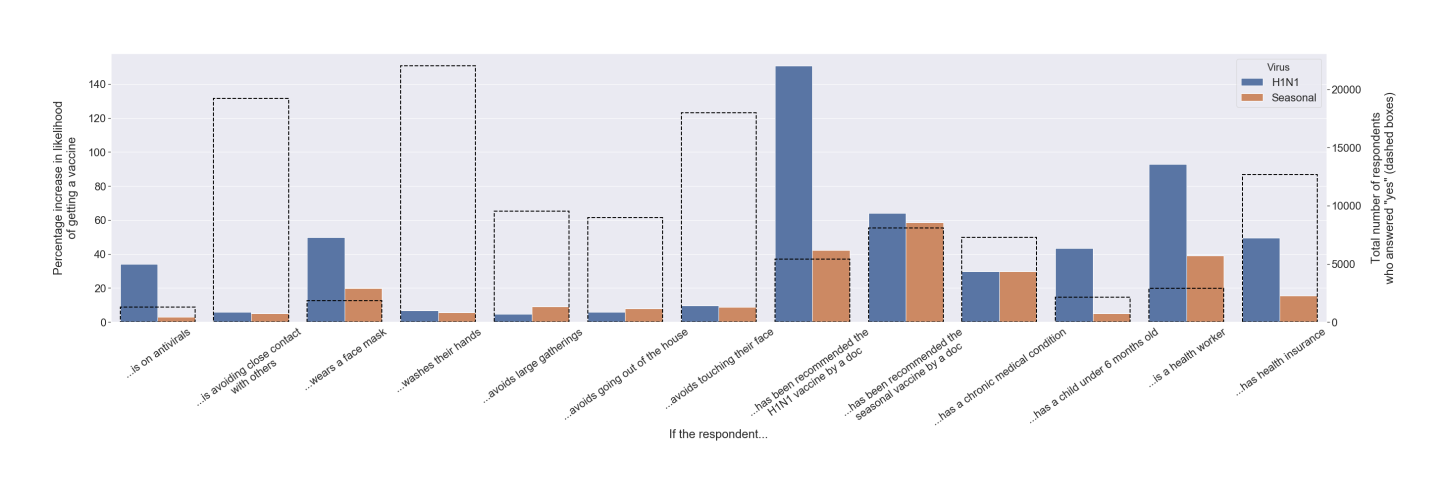

Bearing this in mind, even the exploratory analysis becomes an important decision-making factor. The graph below shows the individual contribution of the various binary questions in determining how likely a patient is to get a vaccine. I reckon that this figure by itself would be more useful in a practical sense that a complex neural network that squeezed out a couple more percentage points of accuracy.

Ultimately, data science does not exist in a vacuum. The creation of a good model is not the end-goal. When creating our models, we need to keep in mind how they are going to be used, and ensure that we do not build them in a way that excludes the expertise of those that will be using them.

(My full analysis of this dataset is available on my github. This article was originally posted on my LinkedIn account)